Generated by ChatGPT

Generated by ChatGPT

Elon Musk has a habit of compressing time. What most people describe as decades, he calls years. What institutions treat as distant futures, he presents as near inevitabilities. The result is often exaggeration. Occasionally, it is also illumination.

Musk lately suggested that humanoid robots could surpass the world’s best human surgeons within three years. The remark, made on the Moonshots podcast hosted by physician and engineer Peter Diamandis, was quickly dismissed by medical experts. Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University, called the timeline “not credible,” pointing to the complexity and variability of human surgery.

Three years is almost certainly wrong. But focusing on the timeline misses the significance of the question Musk was really posing: what happens to healthcare when expertise itself becomes scalable?

Musk’s argument rests on a simple observation. Training a great surgeon takes more than a decade. Even then, human doctors are constrained by fatigue, limited hours and the inevitability of error. Medical knowledge evolves faster than any individual can fully absorb. Machines, by contrast, do not tire, do not forget and can replicate best practices endlessly once trained.

This is not a claim that robots will replace surgeons tomorrow. It is a claim that the bottleneck in healthcare may soon shift from human availability to system design.

That idea feels distant — until it suddenly does not.

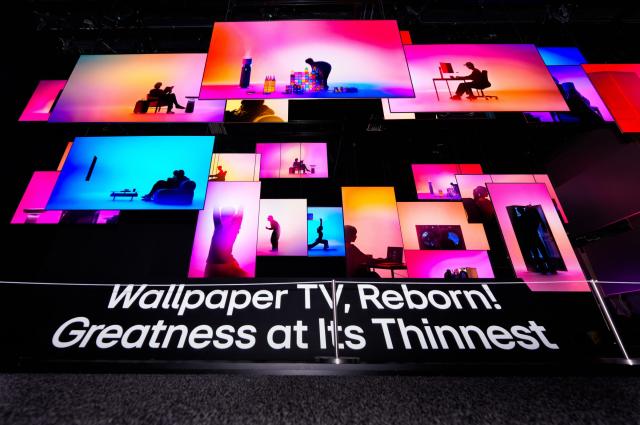

At CES this year, the most consequential advances were not flashy consumer devices but what the industry now calls “physical AI”: systems that can perceive, reason and act in the real world. Humanoid robots are moving beyond scripted demonstrations into logistics, manufacturing and service roles. Robotics firms are no longer asking whether machines can move reliably, but where they should be deployed first.

Healthcare is already on that list.

Robotic-assisted surgery has been standard in certain procedures for years. AI systems now read radiology images with accuracy rivaling specialists. What is changing is integration: software, sensors, chips and mechanical precision are improving together, not in isolation.

This matters particularly in Korea, where the debate over doctor shortages has returned with familiar intensity. Government projections suggest that if current trends hold, Korea could face a shortfall of up to 4,923 doctors by 2035 and more than 11,000 by 2040. The policy response has been predictably narrow: how many medical school seats to add, and how to manage resistance from the medical profession.

The debate is framed almost entirely as a numerical problem.

Musk’s provocation exposes the limitation of that framing. It assumes that the future of medicine will resemble the past — only with more people working harder. That assumption is increasingly fragile.

Korea is not a country lacking in medical or industrial capacity. It is one of the few nations capable of producing the full robotics value chain domestically, from semiconductors to precision manufacturing. Its clinical outcomes in cancer treatment, organ transplantation and cerebrovascular surgery already rank among the world’s best. Korean hospitals routinely train foreign doctors who return home carrying Korean techniques.

The global spread of SMILE LASIK surgery is a revealing example. Initially, the procedure was limited by the skill threshold required of surgeons. Its global expansion accelerated only after Korean clinicians refined surgical planning and execution methods, effectively turning individual expertise into a reproducible system. Today, SMILE LASIK is performed in more than 60 countries.

This is what scalable medical knowledge looks like.

The same pattern appears in medical tourism. The global market is growing at more than 20 percent annually. A routine appendectomy that can cost around $14,000 in the United States is available in Korea for a fraction of that price. Even after travel and accommodation, the cost advantage remains decisive. More importantly, foreign patients are increasingly seeking comprehensive internal medicine and complex care, not just cosmetic procedures.

This suggests trust not only in individual doctors, but in the system itself.

The industrial foundations are already shifting. Hyundai Motor Group and Kia have unveiled on-device AI chips designed for robotics. Boston Dynamics’ humanoid robot Atlas is approaching near-commercial readiness. These technologies will not replace doctors first. They will augment them — extending reach, standardizing precision tasks and reducing burnout.

In such a world, the key constraint may no longer be how many doctors Korea trains, but how effectively medical knowledge is captured, encoded and deployed.

Musk’s three-year prediction may be far-fetched. But his exaggeration is useful precisely because it destabilizes comfortable assumptions.

Korea’s healthcare debate remains anchored in a 20th-century logic: supply versus demand, quotas versus resistance. The harder question — how medicine itself is being reorganized by AI and robotics — remains largely unasked.

That is the question Korea is unusually well positioned to answer. Few countries combine world-class medical outcomes with advanced manufacturing and robotics capabilities. Fewer still have an urgent demographic and workforce challenge forcing the issue.

The future of healthcare will not be decided by how loudly professions defend their boundaries, but by how intelligently societies redesign their systems. Musk’s provocation is flawed, premature and overstated. But it points, uncomfortably, toward a future that will arrive whether the debate is ready or not.

And that, more than the timeline, is what Korea can no longer afford to ignore.

*The author is the managing editor of AJP

Seo Hye Seung 편집국장 ellenshs@ajunews.com

![[포토] 폭설에 밤 늦게까지 도로 마비](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/12/05/20251205000920610800.jpg)

![[포토] 국회 예결위 참석하는 김민석 총리](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110710410898931_1762479667.jpg)

![[포토] 알리익스프레스, 광군제 앞두고 팝업스토어 오픈](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110714160199219_1762492560.jpg)

![[포토] 예지원, 전통과 현대가 공존한 화보 공개](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/09/20251009182431778689.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 관중석 들썩이게 한 끝내기 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.1a1c4d0be7434f6b80434dced03368c0_P1.jpg)

![[작아진 호랑이③] 9위 추락 시 KBO 최초…승리의 여신 떠난 자리, KIA를 덮친 '우승 징크스'](http://www.sportsworldi.com/content/image/2025/09/04/20250904518238.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 최강매력! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.ed1b2684d2d64e359332640e38dac841_P1.jpg)

![[포토]첫 타석부터 안타 치는 LG 문성주](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/02/news-p.v1.20250902.8962276ed11c468c90062ee85072fa38_P1.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 매력이 넘쳐! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.c5a971a36b494f9fb24aea8cccf6816f_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 아홉 '신나는 컴백 무대'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/04/20251104514134.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '아름다운 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/19/20251119519369.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507236.jpg)

![[포토] 발표하는 김정수 삼양식품 부회장](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114206916880.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '순백의 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507414.jpg)

![[포토] '삼양1963 런칭 쇼케이스'](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114008977281.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 하늘 '완벽한 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504457.jpg)

![[포토] 언론 현업단체, "시민피해구제 확대 찬성, 권력감시 약화 반대"](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905123135571578.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '상연 생각에 눈물이 흘러'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507613.jpg)

![[포토]끝내기 안타의 기쁨을 만끽하는 두산 안재석](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.0df70b9fa54d4610990f1b34c08c6a63_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 아이들 소연 '매력적인 눈빛'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/12/20250912508492.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 연장 승부를 끝내는 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.b12bc405ed464d9db2c3d324c2491a1d_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 한샘, '플래그십 부산센텀' 리뉴얼 오픈](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/31/20251031142544910604.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 쥴리 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504358.jpg)